This is the third post in this series about economic evolution. In this post, I want to focus more on the modules that the evolutionary algorithm act upon that I mentioned in the previous post.

Ideas are the most fluffy evolutionary material that spreads between people and organisations. These ideas spread via formal means (like education, formal communications, management decisions or regulations) but also via less formal means like the media, stories, people moving between places and social networks. We pick up ideas as we move around in society, and often we combine these ideas with our own to create completely new idea combinations. I always ask people I interview where they got their ideas for innovations from, and I have heard the most amazing stories of how they took an idea developed in a completely different context and made it work in their own situation.

Tracking how ideas spread in society is tricky, partially because we cannot always remember where we heard or saw something that triggered a thought.

In the first post, I explained that Nelson and Winter (1982:14) preferred to use “routines” instead of “ideas” in their theory as the material that the evolutionary algorithm act upon. Routines are relatively stable ways of arranging physical and social technologies to perform certain functions. Even if they can come about in an arbitrary form, organisations tend to replicate routines internally, and other organisations also copy and adapt routines that appear to work well.

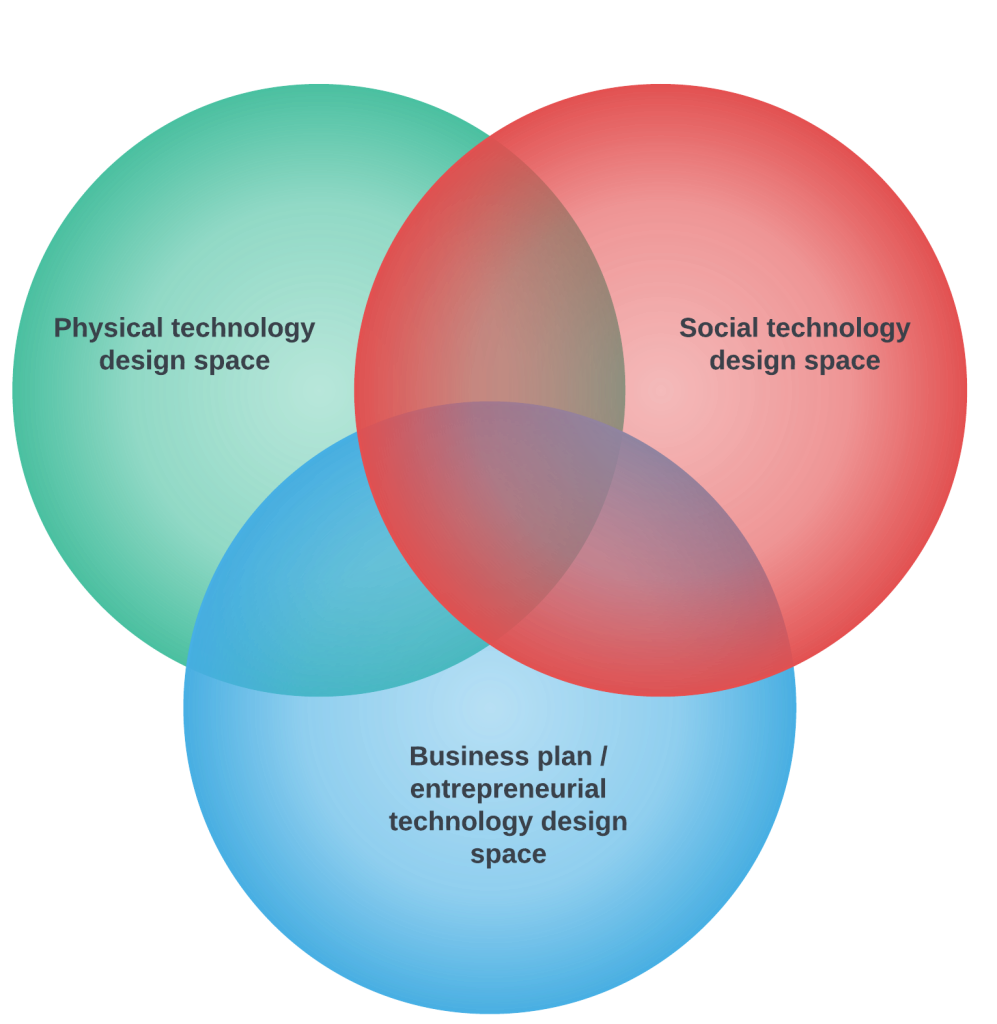

Eric Beinhocker (see the 2nd post) argues for using “modules” as the primary material on which the evolutionary algorithm acts. He agrees with the co-evolution between physical and social technologies but adds that there is a third design space, namely business plans.

“A module is a component of a business plan that has provided in the past, or could provide in the future, a basis for differential selection between business in a competitive environment.” A module is made up of configurations of routines from the physical, social and business plan design spaces.

Beinhocker, 2007:283

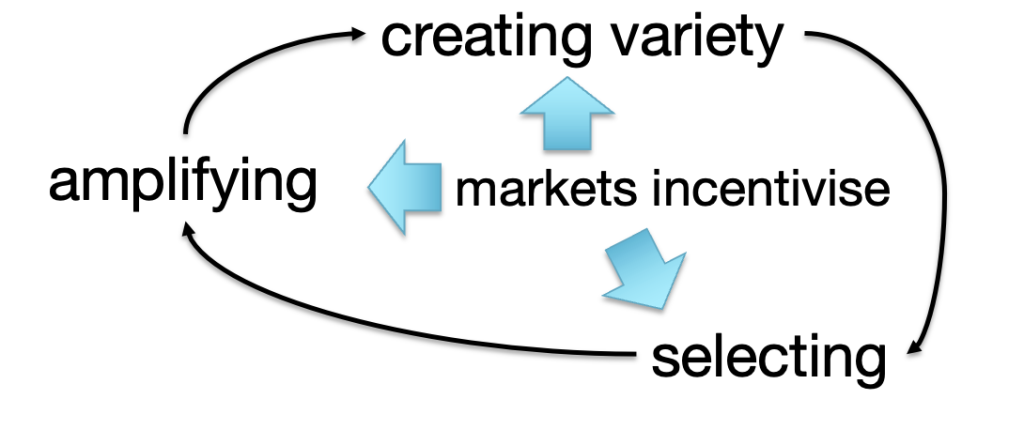

Continuous decisions about the composition of these modules must be made in any organisation or company. These routines and modules can be pretty unstructured, but the theory holds that the better-performing modules will be replicated within and beyond the organisation. In contrast, the less-efficient modules or routines will become obsolete when replicated less. However, even inefficient or unproductive modules can persist due to stubbornness, sunk costs, pride or ignorance.

A challenge we face is that the many internal marketplaces (within organisations) where different concepts or module formulations are pitched against each other do not work effectively. In addition, companies relying on inefficient module configurations can still thrive in uncompetitive marketplaces because the markets cannot select better-performing alternatives.

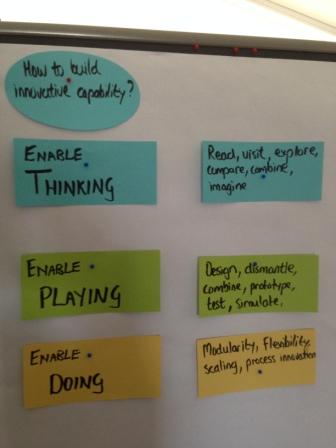

Over the years, I responded to this issue through the instigating innovation series and my teaching at various business schools.

Those organisations that constantly develop or search for new modules or tinker with their existing modules because of anticipated changes in the broader environment can be described as having dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities cannot be bought, it is built through the intentional behaviour of entrepreneurs, managers and employees. David Teece is one of my favourite scholars studying dynamic capabilities, and here is his definition:

Dynamic Capabilities are the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources/competences to address and shape rapidly changing business environments.

Teece et al., 1997, 1990

Teece must often repeat building dynamic capabilities is about achieving abnormal results over the long term. The capabilities part is about the investments in abilities, skills, routines and relationships that are enduring AND that are distinct from what competitors may be doing. The dynamic part refers to the ability to adapt and proactively create market conditions that favour the company. It is about an internal culture of change, experimentation and recognising what works (and what does not work). Why I took this detour is that we need to find ways to foster dynamic capabilities in developing countries in both the public and the private sectors. We have too few organisations actively trying to create new modules that are then adapted based on how they perform in the marketplace.

Back to the main thread. Investments in modules create path dependency, especially when all the investments are along a certain trajectory. In the software and services sectors, companies can change direction faster than in the manufacturing or public sectors. This is mainly due to the way fixed capital is invested in plant, equipment and infrastructure. Once committed to a specific configuration of modules, it may cost a lot of money to change direction.

Whereas routines can often be observed and replicated between companies or contexts, modules are often harder to observe and copy. For example, we can visit a factory and see some physical and social technologies arranged in routines. We can observe how raw material, processes, people and workflows are organised on the factory floor. However, the modular knowledge units combining physical, social and business plans are harder to observe or measure. The hidden parts include the internal incentive structure to innovate and resolve problems, the past learning about what did not work and should never be attempted again, etc., how the factory is connected to suppliers, clients and headquarters, and so on. Some parts of the modules are harder to observe because they weave together past decisions, strategies, funding mechanisms, and future expectations using combinations of physical and social technologies. The machine standing there or how people work together is just the visible tip of the module (or configuration of modules).

The irony is that even management may not realise how much tacit knowledge is involved in the logic that weaves the many different modules combined in a single unit of an enterprise in the modern economy.

From an innovation perspective, there is something else to note about how these modules are created, adapted and disseminated in economic system. The ability to identify, absorb, create and deploy these modules is cumulative. Think of lego bricks. The more modules a specific company has access to or has tried before, the more variations it can create, and the more creative solutions it can select to try in the marketplace.

When this happens over many companies in the economy, markets and users can select from more variety, and better ideas are replicated and amplified in the economy. We know from the research by Cesar Hidalgo, Ricardo Hausmann and the Centre for International Development at Harvard, that these winning knowledge modules can be mapped in the Productspace. (I have a hidden section on my blog site where I have documented some of my experiments and visualisations with this approach – you can access it here).

The experience of selecting combinations or transferring modules to other business areas is cumulative. Companies building modules drawing on different or technological knowledge are better positioned to create entirely new innovative architectures because they can draw on modules from divergent knowledge domains. In contrast, companies that can only manage knowledge modules drawing on narrow knowledge domains are more likely to become specialists. The narrower the range of modules, the higher the risk of being disrupted by other competitors that can build modules on a wider front.

It is not only companies and public organisations that build up these modules. Industries can build modules. Universities play a key role in introducing recent or reliable modules into society. Some modules are described in sufficient detail that can spread via blueprints, technical documentation or software code. Members of online communities can together develop knowledge modules in a distributed way. Just think of the power of Linux or other forms of open-source software that is developed in a distributed way.

Modules can also be accumulated in a society, like the knowledge of how to organise a certain kind of festival, or the modules accumulated through dealing with certain phenomena from the environment. When people change jobs or move from a workplace, they carry with them some understanding of the modules and their sub-routines with them. However, turning some of these modules into a business unit, product or process might require investment in developing the missing business plan areas.

In some locations, office parks or regions, knowledge about certain modules may be developed or may flow more easily over organisational boundaries. Of course, this process may be fostered by developing unique public (or private) infrastructure and through social networks.

I’ll go ahead and conclude. Entrepreneurs, managers, investors and public officials have to intentionally decide where to build modules in their organisations. These modules will typically combine elements from physical and social technology design spaces with business plans. Modules will evolve as they are selected by the organisation (management) and by the market. These modules are cumulative, those that have access to more can also create more variations. Those who draw their modules together from more divergent knowledge domains may have a long-term advantage over those who specialise in building capabilities in a narrower field. Dynamic capabilities are about intentionally investing in capabilities, and continuously evaluating, adjusting and refining existing modules with new ideas from beyond the organisation. Not all the modules originate in a firm, some are present in a community, or a network or are drawn from other companies or contexts. This is easier in some places than in others.

Some questions to explore in your own context:

- In the industries or domains that you work in, what are the modules that you can identify?

- How are they changing?

- Who are the pioneers that are accumulating modules from divergent knowledge domains?

- How do they compare to those mainly focused on developing modules in a narrower field?

- Which public and private organisations have built up dynamic capabilities? In other words, they are constantly reflecting on their performance, and constantly working on building capabilities based on their understanding of their own situation in relation to changes in the broader context. How are these organisations managed, and how does their performance compare to more conventional organisations?

- How are the accumulation and adaptation of modules fostered or promoted in certain areas, knowledge domains or industries?

Please share your thoughts in the comments, or drop me an email.

Image credit

The image at the top of this blog post was created by DALL-E of OpenAI. asked DALLE to create a picture of a topographical landscape with valleys and peaks.

PS.

Here in South Africa, we are all developing modules of how to cope with electricity blackouts (Our government calls it “load-shedding”, which is an excellent way of describing institutionalised incompetence).

Sources:

Beinhocker, E.D. 2007. The origin of wealth. Evolution, complexity, and radical remaking of economics`. London: Random House.

Teece, D.J., Pisano, G. and Shuen, A. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, pp. 509-533.

Teece, D.J. 2019. A capability theory of the firm: An economics and (strategic) management perspective. New Zealand Economic Papers, 53.

Further reading:

If you have access to journal databases, you should also look up the fantastic work of Giovani Dosi, and also Richard R Nelson and B.A Lundvall.

Updated on 5 March 2023 with minor corrections