Originally published in August 2015, revised in January 2018

Reflecting on the correspondence I have received after my previous post and recent training sessions with manufacturers, I have come to realise that people are looking for tools and tricks to encourage innovation in their workplaces. Sometimes it is actually not even about innovation, but about making up for poor past decisions, such as not investing in technology or market development when they should have. Others think of innovation as a function or as a management tool that can be standardised into a job description or an area of responsibility. While this is possible in some contexts, I don’t find this approach to innovation of much use in the smaller and medium-sized manufacturing firms and the research/technology institution space in which I am working.

For me, innovation is firstly a value, a perspective of how organisations should be. When management says, “We are an innovative organisation “or” We want an innovative culture “or” Our reputation is that we are innovative”, then we can move to tools, portfolios, tricks and tweaks (those things that people in innovation functions must attend to). Many textbooks, articles and blog sites on innovation and technology management are then useful. Actually the challenge is to decide which of the bucket loads of advice to use, and consultants such as I typically help organisations to choose a few tools and provide guidance on how to use them fully and consistently. I would dare to say that it is relatively easy to help companies that are already innovative to become more innovative.

What really intrigues me is those organisations that do not think of themselves as being innovative, or that are from industries considered to be traditional and not innovative. Perhaps they used to be innovative, or perhaps they are innovative in some areas but not in others. Perhaps they had one or two tricks in the past that have now become irrelevant. These could be extremely competent organisations, such as a university department, a manufacturer of highly specialised industrial equipment or an organisation that simply designs and manufacturers exactly what its customers order. Even if the outputs of these organisations can be described as ‘innovative’, they do not necessarily have innovative cultures that are constantly creating novel ideas, processes and markets. In my experience these organisations have brilliant technical people, but management is often not able to harness the genius, experience or creativity of its people. The main reason for this is not a lack of technique, tools or tricks, but the lack of an innovative culture, leading to a lack of innovative purpose.

These organisations are trapped. They are equipped for the past, and they are paralysed by all the choices they have to make for the future. For management, it feels as though everything it has in place is inadequate and needs equal attention, ranging from attracting staff with better or different qualifications to finding new markets, developing new technological capability, sorting out cash flow and capital expenditure, and addressing succession planning.

Improving the innovation culture of an organisation is a complex issue. It is not about tasks, functions or tools, but about changing relations between people within and beyond the boundaries of the organisation. Innovation in these organisations is a sideshow, a project, whereas it really needs to be central to the business strategy, a different way of looking at the world.

When working with organisations that must improve their innovative culture, interventions like motivational speeches and optimistic visions of the future are not useful and could in fact deepen the crises facing management. Nurturing a culture of innovation goes far beyond establishing or refining innovation management functions. It is a strategic issue that is initiated by top management, but that will soon spill over into every area of the organisation, hence it cannot be driven by a management function called ‘innovation’.

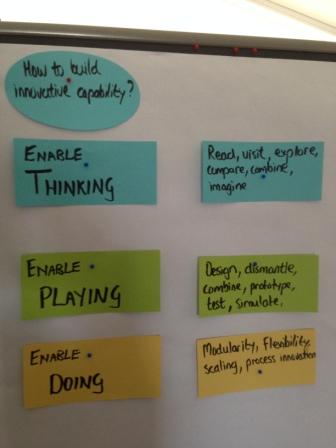

Improving the innovation culture process starts with connecting management back with its people. It starts in the present, the now, not with future scenarios, not with using innovation techniques and better analytical tools, and in most cases not with some or other management fad. It goes beyond trying to improve products, processes or business areas, beyond gaps in management’s capability. It must look at the relations between people, between what people know and can do now (or knew and could do in the recent past), and the potential people see to make small improvements. It is essentially about many dialogues happening throughout and even beyond the organisation. After cultivating dialogue, management needs to empower the organisation’s people to allocate resources to activities that strengthen the learning culture, that turn even small improvement projects into processes that broaden thinking, deepen learning and motivate people to think beyond just their specific tasks.

When management has the courage to decide to improve its culture of innovation it starts a process that cannot be described as incremental improvement, as that sounds too directed. It is rather like a deepening, or an awakening, where employees are inspired to contribute, and management is more aware of what it can do to enable its employees to become more innovative on all fronts. Of course, management faces the risk that outdated management approaches that do not seek to empower employees to be creative will be exposed, and some tough decisions will have to be made.

To nurture an innovative culture requires innovation in itself. It requires management at different levels to rethink its roles from being directive to being enabling, from being top down to being more engaged with its teams.

Like this:

Like Loading...