Originally posted on 23 April 2021, updated on 3 May 2021

Several of my friends and clients are wondering what their workspace arrangements may look like in the future. The lockdowns and disruptions over the past year have rapidly accelerated the use of digital technologies to enable remote work, to improve coordination within and between organisational functions, document sharing and connectivity. Some key experts and managers of some companies are now reluctant to resume work in the office.

Just thinking out loud, I would like to share some of the points that we often have to grapple with about the future of work and workspace. These thoughts are still taking shape, but I would like to share them with you as they may be similar to the points that you are discussing with your teams right now.

- We should think of it as working remotely rather than working from home. Working remotely has now been piloted at scale. Some love it and have vowed never to return to a boring corporate office. Others loathe it and cannot wait to get back to the corporate office. What leaders must consider is that not everybody will be willing to come back to the office.

- The future of the workspace is a hybrid between working in an office and working remotely. Corporate offices are now seen as so 2019. Leaders should engage with their teams to figure out what works best in a shared infrastructure and what works best remotely.

- It is not necessary for people to travel to work for a desk, internet connection and coffee. Leaders must re-think the affordability provided by working remotely and the advantages of working in a shared space. I know of organisations that can now redesign functional workspaces that meet the different requirements of individuals and teams. People want comfortable lounge areas for reading and writing, comfortable tables and chairs for collaboration, cubicles for making calls and deep-thinking work.

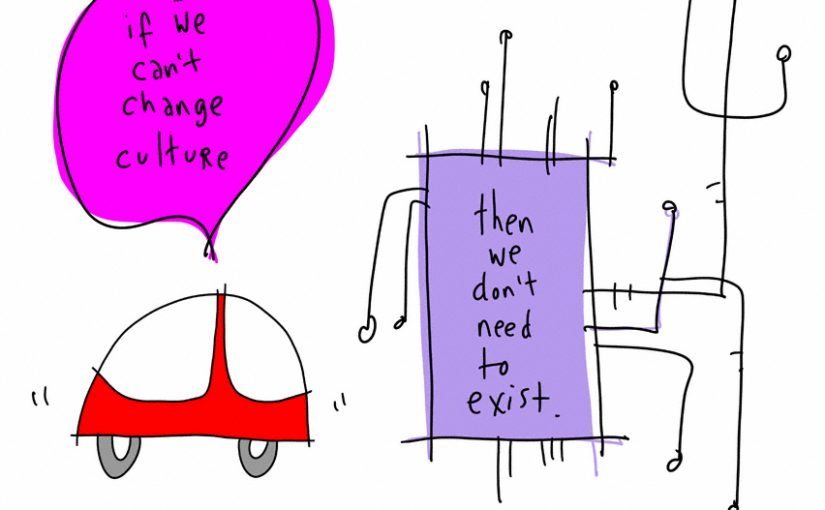

- There is still a role for a corporate or a shared workspace. Not everybody can afford to create and maintain a working environment at home or in a setting elsewhere. Not everyone can perform their functions remotely. Some people simply get lonely and need to connect with other human beings. Others need the kind of equipment and technology that can only be provided and make sense in a shared environment. But there are other soft issues that must also be considered. Innovation culture is shaped by how different people interact and work together. Innovation is hampered by working only with people you like on projects where everybody agrees on what must be done next. Innovation thrives when you bump into somebody from another discipline or department.

Maybe Taylorism (defined by Merriam-Webster as a factory management system developed in the late 19th century to increase efficiency by evaluating every step in a manufacturing process and breaking down production into specialised repetitive tasks) and efficiency have shaped the design of office spaces for too long. Why not create innovative spaces that invite deep concentration (like a lounge or a library), or smaller cubicles for undisturbed work? Or flexible desks that can be re-arranged with good coffee nearby? - While you are busy rethinking the arrangement of your organisation, why not consider placing teams or experts at your clients, or bringing your suppliers or clients into your workspace? The increased use of digital technologies during the past year has led to the discovery of how it is possible for teams from different organisations to work together in completely new ways. I recently listened to an interview with a CEO who explained that their organisation had not only embraced remote work but had also decided to switch to asynchronous meetings! This means that a meeting is recorded, and people who could not participate during the event could still contribute or even challenge what was said afterwards. The use of channels in applications like Slack and MS Teams makes this very easy if used properly

- There are also downsides to working remotely. Just because you use MS Teams does not mean your people feel that they are in a team, or that they are trusted or equipped to do their work. People are zoomed up! At least there were physical constraints that limited the number of people who could participate in a meeting back in the ”old days”. Now with digital communication tools, meetings are being held more frequently with more people participating. A friend told me that she spends her evenings working because her days are filled with Zoom meetings.

- Lastly, working remotely is not for everybody. Here in South Africa, creating and maintaining a remote workspace is also often determined by your race, your age, where you live, and who lives with you. Where you live determines internet speed, the reliability of the electricity supply and also how long and safely you commute to an office. We live in a leafy green suburb which is a fantastic environment to work in. But a colleague whom I work with lives in a small apartment with two other professionals sharing the same space and internet bandwidth. While some individuals enjoy working at their own pace, others need to be supervised. For younger employees the socialisation process of working with older and also very differently skilled people is critical.

I would love to hear from you about what you have been grappling with, or what you are debating to do right now.

- Have you redesigned your workspace, or renegotiated how certain processes work?

- Have you made up your mind whether you are going back to the “office”, or do you prefer working remotely?

- Has somebody on your team decided to not come back and to work remotely, or even worse, to resign because they prefer to work remotely?

- Which tasks would you prefer to perform remotely and which in a physical office space?

If you would rather not reply on this blog post, you can send me an email.

Here are some interesting resources by others:

In interview #100, Shane Parish interviews the co-founder of WordPress Matt Mullenweg. Head over to https://fs.blog/knowledge-project/ for more information

In episode #784 of the HBR IdeaCast, Anne-Laure Fayard talks about her HBR article “Designing the hybrid office”

A special thank you to Natasha Walker and Sonja Blignaut for the conversations and the encouragement that made this blog post possible.

Image by DarkmoonArt_de from Pixabay

the organisation. This includes looking at technologies that could affect the clients of the organisation, and technologies that could disrupt markets and industries.

the organisation. This includes looking at technologies that could affect the clients of the organisation, and technologies that could disrupt markets and industries.