This is the fourth post in this series about economic evolution. In this post, I will look at the co-evolution between companies and the broader institutional environment they form part of.

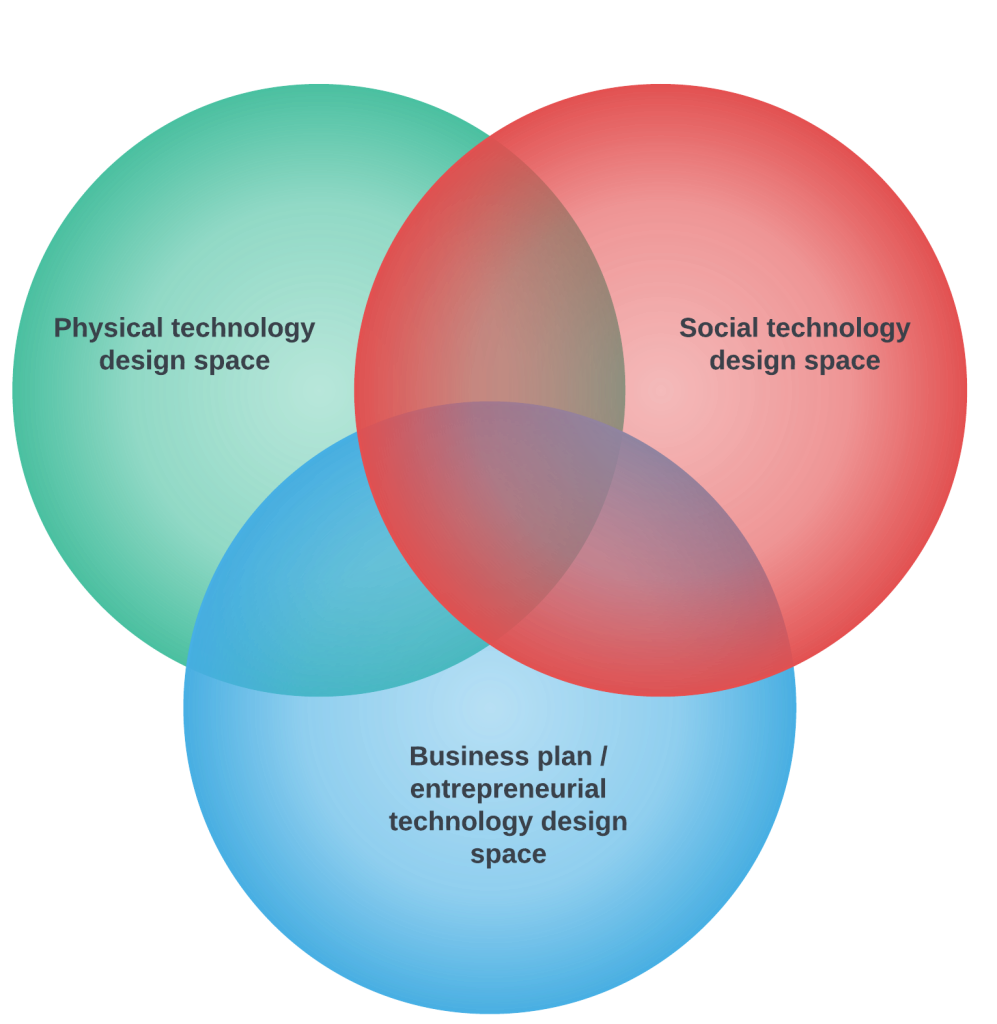

Towards the end of the 2nd blog, I mentioned that the design spaces within firms (and organisations) interact with different design spaces beyond their boundaries. The available “technology” modules within any organisation, private or public, interact with and are shaped by technology the modules available in the institutional landscape. The technology in the preceding sentence should be understood as “knowing how to do or achieve something specific consistently”. For example, think of the trust system needed for two companies to transact with each other. Perhaps they rely on the social institution of social relations. This worked for most economies for a long time. But with increasingly sophisticated products and services and also the more impersonal nature of many transactions, contracts and their enforcement through a legal system is increasingly important. To further make impersonal transactions smoother, standards, performance criteria and branding are all social institutions that have evolved to enable transactions.

These institutions, including the norms and the organisations that provide related goods and services, evolve with the economic transactions they enable. In some cases, the institutions lead the evolution by providing the economy with new knowledge modules or services. In other cases, unmet demand might lead to an institutional response. Yet in another case, policymakers might design policies to shape the institutional offerings or the demand patterns.

The broader institutions and economic activity co-evolve.

I want to take this further by focusing on the meso space and how this space co-evolves with industries, locations or communities.

The meso space is a design space where interventions are designed to address the persistent patterns in the economy. Most microeconomic transactions occur via markets, hierarchies or networks, and each of these forms of allocation have strengths and weaknesses. All three can fail. When a particular kind of failure persists, this can be called a market failure, management failure (for hierarchies), government failure (in the case of public services failing), coordination failures or systemic failures. The meso space is where stakeholders intentionally intervene to address or respond to persistent failures.

Because it is sometimes not helpful to use labels like market or government or systemic failures, we often describe these patterns as “patterns of underperformance”. These are the patterns we often see when we look closely at an industry, value chain, location or national economy.

Some meso interventions may be targeted at a particular industry, a technology, a region or a specific pattern. In contrast, others may target whole policy areas like industrial, technology, trade or locational policies. While most meso interventions are supposedly intended to deal with negative or problematic patterns, there is no reason that meso interventions can also be designed to leverage positive characteristics. That is exactly what many tourism or investment promotion strategies aim to do.

Meso interventions might be a policy, project, programme, service, or organisation. Sometimes an existing organisation might launch a new service or provide additional functions to address a particular pattern of underperformance in the economy. This, in turn, might result from a particular ministry deciding to create a policy to address a particular issue, like deciding to invest in an incubator to develop particular solutions the company might be interested in. I know this might sound unclear, but when a policy or strategy is specific in its focus, we describe it as a meso instrument. In contrast, macro policies and strategies are more generic and are not specific to an industry, technology or location.

The public sector is a dominant actor in the meso space. However, in most countries, the public sector does not act like one stakeholder. There are different government departments and publicly funded agencies, at different levels, all with different jurisdictions or mandates. Just like coordination failures can occur in the private sector, coordination failures within different public functions can paralyse a country, industry or location.

However, not all meso policies and interventions are about the public sector trying to be the benevolent private sector supporter. Companies can also design policies that shape the economy around them. For instance, a large manufacturer might have policies to develop their supplier networks, to make the location where they are based more attractive, or to support particular public interests. Not-for-profit or non-governmental organisations can also have development policies to address particular economic patterns. So meso policies and programmes can be designed or implemented by the public, private or civil sectors.

While some economic development practitioners are often biased in favour of addressing market failures, the meso space must often also address government and other systemic issues. For instance, the meso space is often critical to designing or implementing programmes to reduce inequality, provide more effective public goods, reduce coordination problems, maintain and expand critical physical and digital infrastructure and address other social priorities.

Suppose a persistent pattern of decline plays out in a location or an industry over time. For instance, let us imagine that the city centre and its key economic activities are in decline. It is unlikely that this pattern of decline can be addressed by only the public sector implementing a few projects. Most likely, the pattern can only be arrested by mobilising many different public, private and civil organisations and then pursuing projects together for extended periods. Interventions aimed only at the private sector are unlikely to work by themselves, as renewal and investment in public organisations, civil and social infrastructure would mostly likely also be required. The location will change as the economic activities of enterprises and the supporting institutions co-evolve. In most cases, this is a process that takes time.

This example illustrates how industries and institutions co-evolve. As the city centre declines, social institutions and networks might also decline. At the same time, new informal economic activities might arise in the place, but this might lead to an acceleration in the decline of formal economic activities. Renewal in public, private and civil organisations might be needed to reverse this trend. At the same time, investments in public infrastructure and attracting private investment are needed. These kinds of initiatives will shape the incentive landscape for investors, individuals and entrepreneurs, just as the kinds of investors, individuals and entrepreneurs might play a role in deciding where to start or what to do.

It is impossible to fix persistent patterns of underperformance in the private sector through the private sector alone. This is at the heart of systemic change: the recognition that firms and their meso landscape of interventions, programmes and organisations co-evolve. Sometimes we start with the firms and then try to invigorate the meso landscape. At other times, we may start with the meso landscape and try to make it more resilient, innovative or valuable to the private sector, the community or the location. But we also have to think both of the micro level where transactions take place via markets, networks and hierarchies, as well as the meso landscape where incentives, investments and coordination takes place. Any systemic intervention would typically involve coordinating the development efforts of the public, private and civil sectors over extended periods.

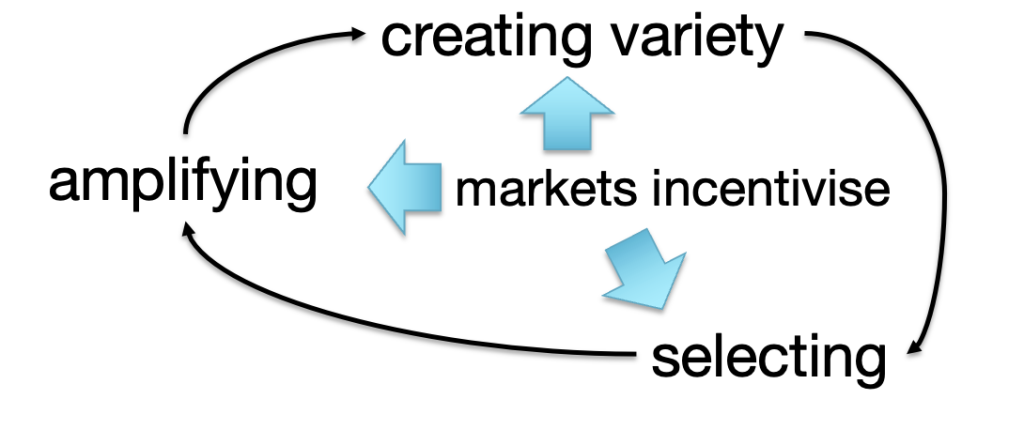

The challenge is that co-evolutions are not designed ex-ante, although it is possible to catalyse changes in the public and the private sector if there is enough willpower and incentives for change. Every small change creates further opportunities for change by making knowledge or technology modules available. Any idea or modules that become available in the economy, even if it was meant for a specific purpose, becomes part of the substrate of ideas that others can use in new combinations to innovate or transact. This may lead to a further changes in public policies, or to further changes in the institutional landscape, which in turn may lead to additional services or technologies becoming available to the economy.

This is how industries, institutions (both norms and organisations), technologies and locations co-evolve. They contribute knowledge modules or functions to the economy, that others can combine with to create value. And so it goes on.

If you think of the context where you are working, can you see examples where changes in the private sector (performance) lead to changes in the meso landscape or the other way around? Where did new or adapted services from the public meso programmes shape a location, industry or technology? Can you think of any unintended consequences or benefits, in other words, that was not designed intentionally but happened because of preceding changes?

Alternatively, where did changes in the private sector result in adaptation or changes in the public sector?

Lastly, can you think of examples where a civil or not-for-profit organisation’s behaviour (or interventions) resulted in public and private sector changes? How did the system co-evolve as a result?

You are welcome to share your thoughts in the comments below. Or just continue sending your comments to me by email or social media. I value your comments and suggestions.

Image credit: Image created by DALLE on 22 February 2023. The prompt was to create a drawing showing the relationship between urban planning and universities.