This is a continuation of my blog posts based on my research into how technological disruptions and change occurs.

A widely publicised model is the S-curve model that enables the evolution of the performance of a technology (Foster, 1986a; Foster, 1986b). In management of technology textbooks, this model is used to make predictions about the evolution of the rate of technological change, to detect possible technological disruptions, or to determine the limits of a particular technology.

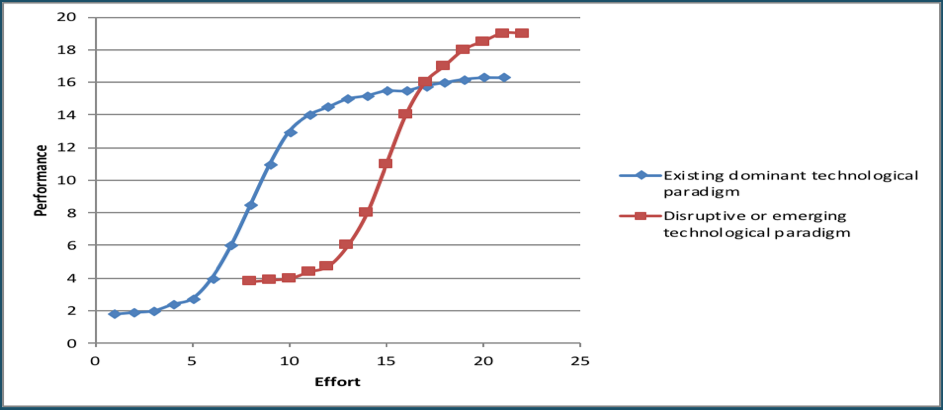

In the S-curve model[1], the Y-Axis tracks the performance of a specific technology, while the X-Axis shows effort measured in R&D investment and resources aimed at technology development (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: A technology S-curve

Source: Author, based on work by Foster and Christensen

In the beginning of the development cycle of a specific technology, it takes a lot of effort to get performance increases out of a technology (blue line in Figure 4). This phase is often characterised by many different competitors with many different approaches to solving a given technological problem. This is often followed by an exponential improvement curve where the effort pays off with large increases in performance. Typically, improvements to the performance of the technology at this point in time are driven by several incumbent competitors, with many companies if their technologies are not chosen. After a while, the performance increases for every unit of investment (effort) starts to taper and return on investment diminishes. This is where incumbent firms are most vulnerable, as they try to squeeze as much profit from their existing technologies without looking for new investment opportunities even though they are almost completely dominating the market. New entrants find it very difficult to challenge the incumbents in the existing market place, because the incumbents have established a brand reputation, distribution networks and supporting systems.

Clayton Christensen (2000) explains that incumbent firms are often overconfident about the value of their existing technologies and tend to ignore potential new technological approaches. New entrants that are using a different technology aimed at a different market segment might be entering a new steep S-curve (the red line in Figure 4).

The new technology is usually at a lower level of performance than the original technology, and targeting a small, not-so-profitable niche that the incumbent firms are not willing to fight for (as they are benefitting from the scale of their current customer base). The niche market provides the new technology space to innovate in ways to increase in performance, and at some point, the graphs may intersect. This is where whole industries or technologies can be disrupted, as existing customers switch to a new technology that is in an upward performance curve. Christensen and Raynor (2003) explain that incumbents are very often “relieved” to exit small, low-margin markets, and so they constantly upgrade towards higher-margin or higher-volume target markets. This leaves small niche markets for new entrants where demands are not being met. These niche buyers and the new entrants often work together through several development iterations together, until the performance curve of the new technology crosses the incumbent technology in the broader market.

Christensen argues that whether a technology is disruptive or not depends less on how radical it is, but more on its specific effect on the S-curve. If a new development improves performance of an existing technology, then the incumbents are preserved and tend to benefit most as this improvement often suits its current scale of operations. If a technology creates a new S-curve, then it may disrupt existing technology at some point, leading to a disruptive change in industry structure. This implies that radical or incremental performance improvements in most cases benefits incumbents, while disruptive innovation challenges industry structures. In an interesting twist, Christensen argues that incumbents are not ignorant of new technologies and underserved markets. He argues that they are the victims of their own success in making decisions that leverages existing knowledge, networks, markets and capabilities. Ironically, customers may actually communicate that they prefer incremental improvements on existing technologies rather than adjusting to disruptive technology. It is not only the innovator that faces risk and uncertainty, buyers also try to avoid making decisions about technologies that are only emerging, or where performance, results and requirements are vague or uncertain. Decision-making in research and development may also be biased towards the most likely-to-succeed ideas that directs resources away from tinkering or experimenting with fundamentally different ideas.

Existing companies may be able to spot an emerging technology or group of technologies with a potential to disrupt their current market. However, it may still be very difficult to decide when to switch more resources to completely new technologies that may also require different business structures, culture, market and supplier relations (thus switching resources from the blue line to the red line in Figure 4). The performance of the technology is born from the strategy of firms and how they allocate resources to product, process and business model innovation. One way that governments can reduce the costs of incumbents and new innovators to confront, investigate and test new technologies is through technology demonstration and applied technology research, where companies can visit, use or test technologies hosted by public universities. Because companies know that their competitors might be investigating the feasibility of trying a new technology, they themselves are more likely to invest in new skills, in trying the new technology or exploring how this new technology could result in new markets, business models and capabilities.

Gathering all the information that is necessary to construct an S-curve requires time and can be costly. It is especially difficult to figure out which performance criteria and measures of effort to use to construct the graph. However, when a portfolio of technologies is tracked this way it shows not only inflection points, but when certain technologies may outperform existing dominant technologies. A key question that must be answered in constructing this model is whether to track performance change at the level of components (modules), sub-systems or architectures. Furthermore, even if the performance lines cross, incumbents may not switch if their sunk investments are too high, or the learning cost of the new technology is too high. That is why newer companies are needed in the economy, as they might have lower sunk investments and more to gain from higher performance. Over time, resources shift from the old technology to the new, but only if the new technology is accepted and is disseminated sufficiently.

A critique of the S-curve model is that while the graph makes sense, it is often hard to construct and project into the future. It often makes sense ex-post to explain why a given technology outperformed a previous dominant technology. Also, a weakness of the narrow focus on technological performance disconnects the technology from the broader technological and social context, such as the organisation capacity and supporting networks and infrastructure that is required to make a given technology work.

Notes:

[1] It is called an S-curve because when the results are graphically illustrated the curve that is usually obtained is a sinusoidal line that resembles an S.

Sources

CHRISTENSEN, C.M. 2000. The innovator’s dilemma: when new technologies cause great firms to fail. 1st Ed. New York, NY: HarperBusiness.

CHRISTENSEN, C.M. and RAYNOR, M.E. 2003. The innovator’s solution: creating and sustaining successful growth. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

FOSTER, R. 1986a. Innovation: the Attackers Advantage. New York: Summit Books.

FOSTER, R.N. 1986b. Working The S-Curve: Assessing Technological Threats. Research Management, 294 17-20.

Citation for this text:

(TIPS, 2018:23-24)

TIPS. 2018. Framing the concepts that underpin discontinuous technological change, technological capability and absorptive capacity. Eds, Levin, Saul and Cunningham, Shawn. 1/4, Pretoria: Trade and Industry Policy Strategy (TIPS) and behalf of the Department of Trade and Industry, South Africa. www.tips.org.za DOWNLOAD